Did Scientists Actually Build a PlayStation 2 Supercomputer?

Swapping SSX Tricky for black holes

“It’s Tricky to rock a rhyme, to rock a rhyme that’s right on time, it’s Tricky!”

You can feel the controller vibrating in your palms. It’s the dawn of the new millennium and you’re tearing down the Elysium Alps as Elise. Fresh snow sprays against the camera while fireworks explode above crowds screaming your name.

The board slices through the powder leaving a crisp, flattened trail. The audio shifts, with the crunch of the snow changing perfectly depending on the terrain beneath your feet. Rahzel insists you, “Call your mama in the room and show her how great you are!”

But while we were all busy mastering Uber Tricks in SSX Tricky, the rest of the world was starting to lose its mind. With the 24-hour news cycle in full swing, the media was desperate for a fresh nightmare.

They found their new monster in the PlayStation 2. It was that black, monolithic slab of silicon sitting right under your TV. How? Well, rumors began to spread that Iraq was stockpiling thousands of consoles to strip them for parts.

The rumors were baseless, of course, but that didn't stop various outlets from running with the story. It was a classic case of the media spinning a narrative out of their own fear of teenage hobbies.

“An integrated bundle of 12-15 PlayStations could provide enough computer power to control an Iraqi unmanned aerial vehicle, or UAV.” - Eurogamer, 2001

The idea was that a cluster of these consoles could actually power the guidance system of a long-range missile. It felt like a bad straight-to-DVD thriller, and officials did eventually debunk it as pure tech-illiterate hysteria.

But that underlying fear? It wasn't entirely misplaced.

The PlayStation 2 was an absolute monster at certain tasks. Sure, it could run SSX Tricky at a flawless 60 frames per second, but its true potential went far beyond gaming. Three years later, inside a quiet laboratory in Illinois, someone finally proved exactly what that hardware could do.

If you enjoy my work and want to support it, consider buying me a coffee. It helps keep the words flowing and the ideas brewing!

I dug into the archives of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois. This is the place that gave us the Mosaic web browser. They deal in serious hardware, because well, they often dabble in serious problems.

But the team at NCSA hit a massive wall. They needed to crunch numbers for quantum chromodynamics and gravitational waves, which is basically the "final boss" of math. Or so I’m reliably informed by a three-minute YouTube deep dive I watched while half-asleep.

We’re basically talking about the kind of heavy-duty simulations used to model black hole collisions. Normally, you’d just go out and buy a multi-million dollar supercomputer for a job like that.

But the NCSA team was operating on a budget so small it wouldn't even cover the voice acting for a minor side quest in Final Fantasy X. And that’s when they looked at the PlayStation 2.

Let’s Get Emotional

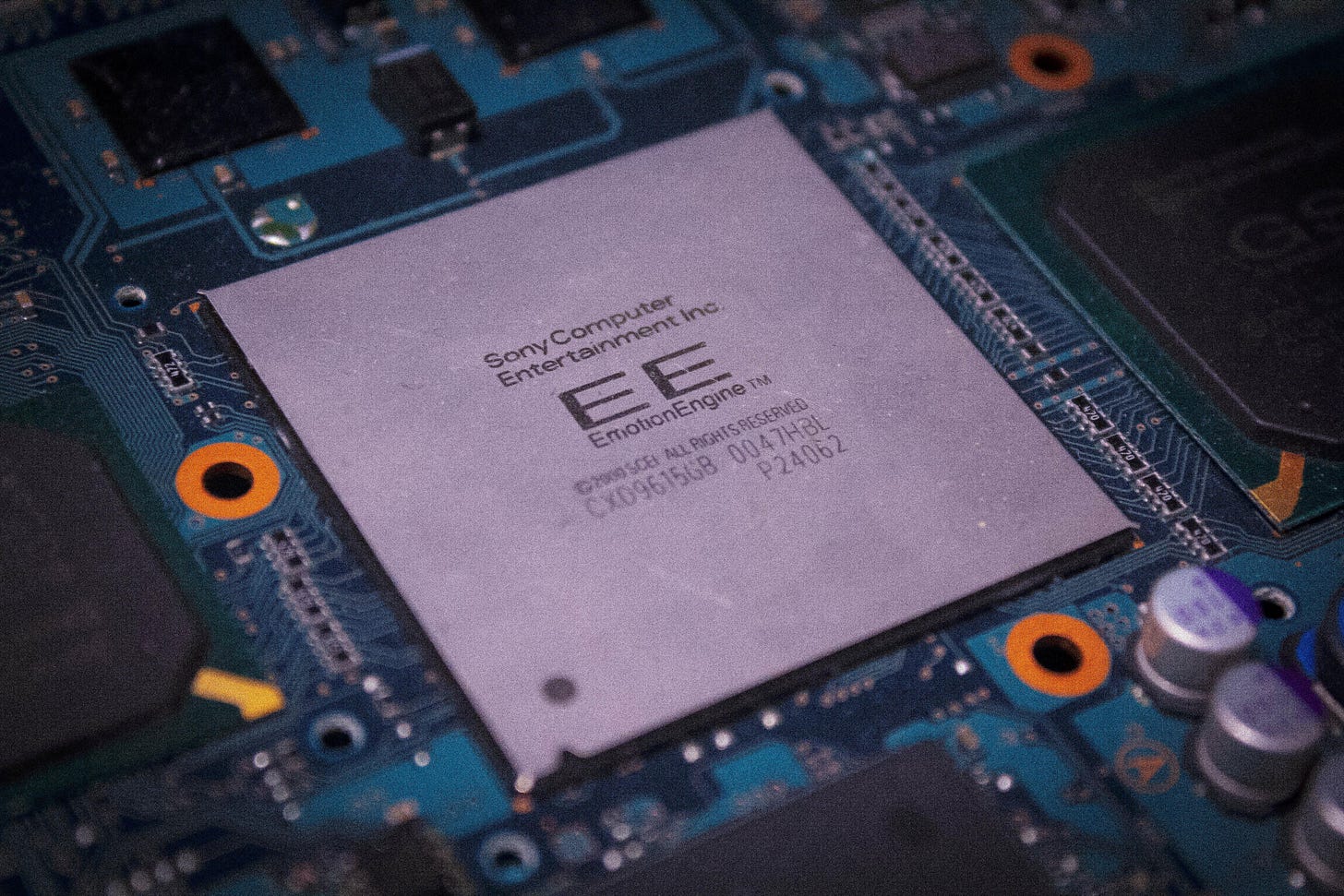

The Sony PlayStation 2 was around $199 at the time. Inside that black plastic shell was the Emotion Engine. You might have heard of it, and it was a big deal around the time of the PlayStation 2 release.

This processor was unique. It was an 128-bit wafer designed to push vector math faster than almost anything else on the consumer market. And so the researchers crunched the numbers and crunched them some more. The conclusion was that a cluster of standard PC servers would cost a fortune. A cluster of PS2s would cost pennies in comparison.

So they went shopping.

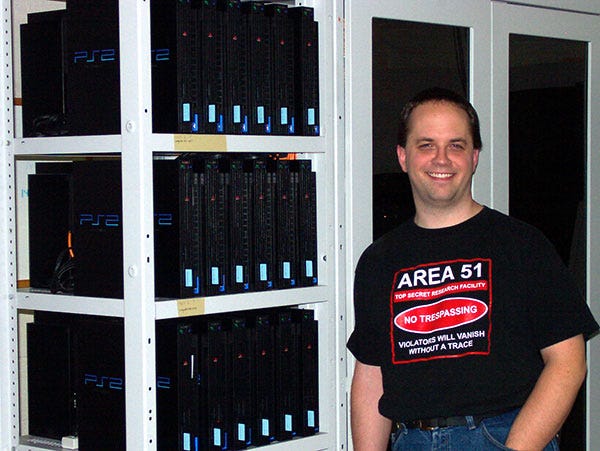

The team didn't reach out to Sony for a partnership or a sponsorship. Instead, they just went out and bought them. Can you imagine the look on a retail worker’s face when they walked in to ask for seventy consoles?

After walking away with all the hardware they needed, they also bought 70 copies of "Linux for PlayStation 2". This kit was the key. It allowed them to bypass Sony’s locked-down operating system and transform each console into a raw Linux node.

“This is literally a hand-made supercomputer assembled by a creative group of researchers who are constantly pushing the limits of our field.” - Dan Reed, director of NCSA.

They ripped the consoles out of the boxes. They then placed them on metal racks, and wired them together using high-speed network switches made by HP.

The total cost was roughly $50,000. A comparable supercomputer would have cost five or ten times that amount.

Reed continued, “Many people have talked about the possibilities of the PlayStation’s graphic processors, but to our knowledge, no one else has attempted to make these machines perform as a large, integrated Linux cluster. We have shown it is possible, and the long-term result could be another low-cost computing alternative for the scientific community.”

Frankenstein Cluster

This wasn’t some viral stunt. It was a functional scientific instrument. The "Frankenstein Cluster" ran legitimate, high-level code. And as it turns out, the Emotion Engine was surprisingly elite at the specific matrix multiplication needed for physics simulations.

It actually worked.

For a brief period, one of the most powerful computing clusters in the academic world was powered by the same hardware that 12-year-olds were using to play Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 4. The photos of this setup are surreal.

You expect a supercomputer to look like a monolith. You expect blinking lights and chrome. But this looked like a cluttered teenager’s bedroom multiplied by seventy. You can see the standard retail Sony logos. You can see the memory card slots. It is a wall of black plastic bricks.

There is something darkly funny about it. These machines were designed to simulate fantasy worlds, they were built to render ‘dragons and explosions’. But these scientists forced them to simulate the crushing gravity of a dying star.

It worked, even if the whole setup felt magnificently out of place.

The NCSA eventually retired the cluster. Hardware evolved. Commodity PCs became cheaper and faster. The PS2 became obsolete. But for a moment, the barrier between ‘toy’ and ‘tool’ vanished.

‘Despite the computing promise of game consoles that sell for less than $200, the researchers acknowledged that the experiment was likely to be most useful for a group of relatively narrow scientific problems.’ - New York Times, John Markoff

I think we often underestimate the tech we own.

I also think this highlights how the devices we use for entertainment are often capable of much more than we imagine. The PlayStation 2 pushed the limits of consumer hardware, but its successor, the PlayStation 3, took things even further with its famously complex internals.

The last of its kind before the PlayStation 4 and 5 opted for less bespoke and more conventional hardware.

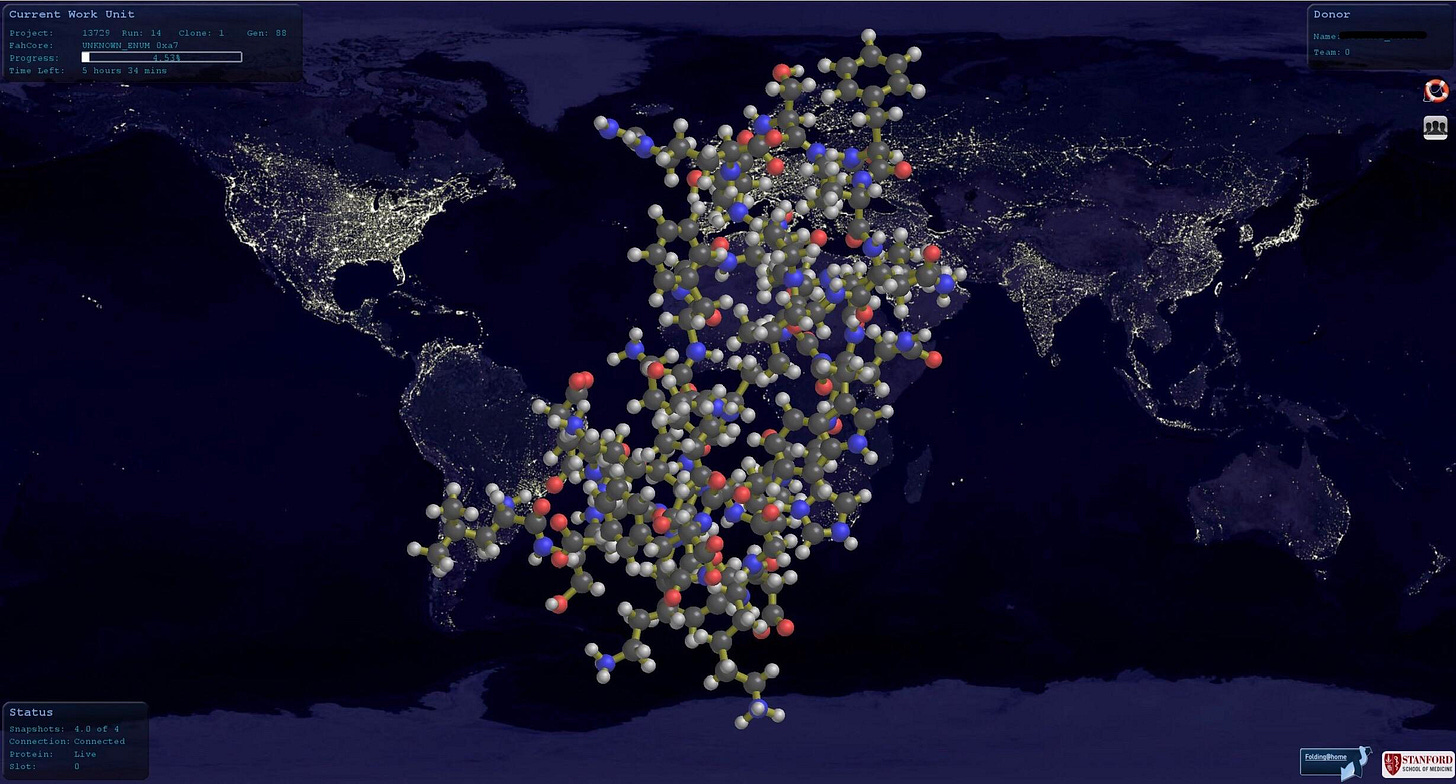

The PS3 also eventually served science in a way that was both similar and entirely new through Folding@home. Instead of a few researchers chaining consoles together in a lab, millions of gamers used their PS3s to join a massive, global distributed computing network.

While you slept, your console was crunching data to help scientists understand protein folding and search for cures for diseases like Alzheimer’s and cancer. It was the final chapter of an era where the gaming box in your closet could double as a dormant monster of a supercomputer.

I’m getting emotional just thinking about it.

If you enjoy my work and want to support it, consider buying me a coffee. It helps keep the words flowing and the ideas brewing!

Brilliant piece. The juxtaposition of consumer gaming hardware solving astrophysics problems really underscores how arbitrary the distinction between 'toy' and 'scientific instrument' can be. What I find most interesting is that NCSA didnt need permission or partnerships, they just bought retail consoles. That democratization of compute power, where $50k could rival multimillion dollar setups, foreshadowed distributed computing in ways we take for granetd now. Back when I was doing grad research we actually considred using PS3s for simulations but ended up goin with AWS instead.

So interesting! Love the idea of 90s parents buying their kid a PS2 to play Spyro or whatever without realizing that they just handed their 9 year old a supercomputer capable of doing this.